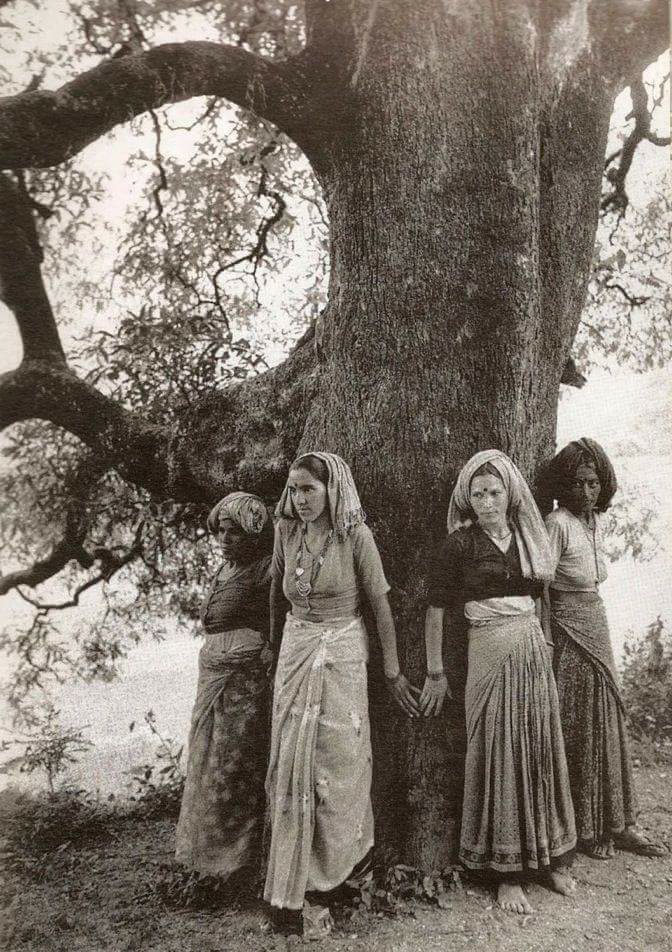

She has her own secret woodland at home in Surrey, where she has been planting trees for 30 years, initially with her husband, Michael Williams. He died in 2001 and there’s a tree here in his memory. Many of Dench’s friends are remembered in trees. “It’s something living that goes on,” she explains. “You don’t remember them and stop; you remember them and the memory goes on and gets more wonderful.”

Better than a bench, then, in that respect. And it can always be turned into a bench, at some point – hundreds of years maybe – down the line. My dad has a quince tree in Suffolk. Actually, he planted it himself, but it became a favourite and later we scattered him around it. I like to think that he continued to help it grow, but I don’t know if the science and horticulture back that one up.

Dench wants to find out more about trees, and what they do through the seasons, from the experts. So a man called Tony takes her to meet a yew that is about 15,000 years old. That tree has seen a lot in its life. It was even shot in the English civil war (the cannonball was found inside it). Yews are interesting because they are poisonous and because some people say they have experienced hallucinations while among them. Cool … who’s coming down the churchyard to take deep breaths and maybe see some ghosts?

She does a lot of that in this – gasping and gushing, saying how wonderful it is. And dropping in a few lines from Shakespeare’s sonnets:

“From you have I been absent in the spring

When proud-pied April, dressed in all his trim

Hath put a spirit of youth in everything …”

Dench clearly adores trees and sees them in a very romantic and personal way. She is delighted when she learns that they can communicate by sending messages to each other underground. “I think of my trees as part of my extended family,” she says about her own woodland.

But it’s not just about the poetry, the gushing, the departed actor friends and the making of new, deep-rooted ones. There’s science, too. We learn that trees can sense attack from insects or from deer and change their taste to be less palatable – and even call out chemically for outside help – which is fascinating and extraordinary.

There are lots of facts and stats, too. Dench’s oak, for example, has 12km of branches and there are more trees on the planet than stars in our galaxy. And more deer in Surrey now than there were in the time of Elizabeth I. That’s amazing, isn’t it? Although my favourite stat of all is that aphids reproduce so prodigiously that in one year an aphid can give rise to 600bn of the little buggers. Call in the ladybirds.

You want history and English lit as well? You got it because this isn’t just about the role trees play in our landscape, our environment and in Dench’s life. It is about how they have been used to make longbows, build warships and steer the course of history. And it’s about trees’ role in literature … well, Shakespeare because that’s Dame Judi’s other passion. Shakespeare’s woods are often full of menace and magic, but also romance.

Tony has a nice ancient Chinese proverb: the best time to plant a tree is 50 years ago; the next best time is today. Dench heeds the advice and plants two, both English natives. The yew will be in memory of Robert Hardy, actor, friend and expert in longbows – which, of course, are made of yew. And the other – an oak – she doesn’t say who that one’s for. Perhaps it’s for herself, an oak for Judi Dench.

Since you’re here…

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. The Guardian is independently owned. That means we don’t have a billionaire owner funding us but it also means we increasingly rely on contributions directly from our readers.

The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as £1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

SOURCE: THE GUARDIAN